Peggy Duff (1910-1981) served as the first Organising Secretary and later the first General Secretary of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament. She was a firm and active supporter of the END campaign in the 1980s. This article forms Part I of her chapter in Eleventh Hour for Europe, Edited by Ken Coates and published by Spokesman in 1981.

* * * *

Introduction

The Non-Proliferation Treaty which was finally agreed in 1968 and came into operation in 1970 was described by Alva Myrdal in her book The Game of Disarmament (Spokesman, 1980) as “a grossly discriminatory treaty”. “Obligations”, she wrote, “were laid on the non-nuclear weapon countries, and only on them, to accept international control over nuclear installations. In the end they were able to extract only a promise (Article VI) from the superpowers to negotiate in good faith the cessation of the nuclear arms race at an early date.”

“There was no balance, no mutuality of obligations and benefits. I said then that it was necessary to emphasise the reluctance of the non-nuclear powers to shoulder a particular and, as matter of fact, a solitary obligation to make renunciatory decisions in regard to proliferation of nuclear weapons. To place the major responsibility on their shoulders amounted to a clever design to get the NPT to function as a seal on the superpowers’ hegemonic world policy.”

The First Review Conference of the Non-Proliferation Treaty in 1975 did nothing to remedy these deficiencies. The Second Review Conference will take place in Geneva in August 1980, however, at a time when pressure for disarmament from many of the Non-Aligned Countries and from movements have increased and many of the processes for negotiating disarmament have improved, as a result of the UN General Assembly Special Session on Disarmament in 1978.

It is, therefore, very important that movements concerned with disarmament should join with states genuinely committed to it in seeking to change this imbalance between the obligations of the Non-Nuclear-Weapon States (NNWS) and the Nuclear-Weapon States (NWS). To do this effectively, we have to understand what are the essential issues to which priority should be given.

We will examine the security aspects, that is, the limitation and disarmament measures required not just to prevent a dangerous increase in the number of nuclear-armed countries, but to control the nuclear arms race between the superpowers: an obligation which is only minimal in the Treaty and which has only too clearly been avoided. We have to pinpoint not only the sort of security guarantees that should be given by the nuclear superpowers to countries that renounce nuclear weapons, but also the most important disarmament measures that ought to be rapidly agreed, if the threat of nuclear weapon proliferation is to be countered.

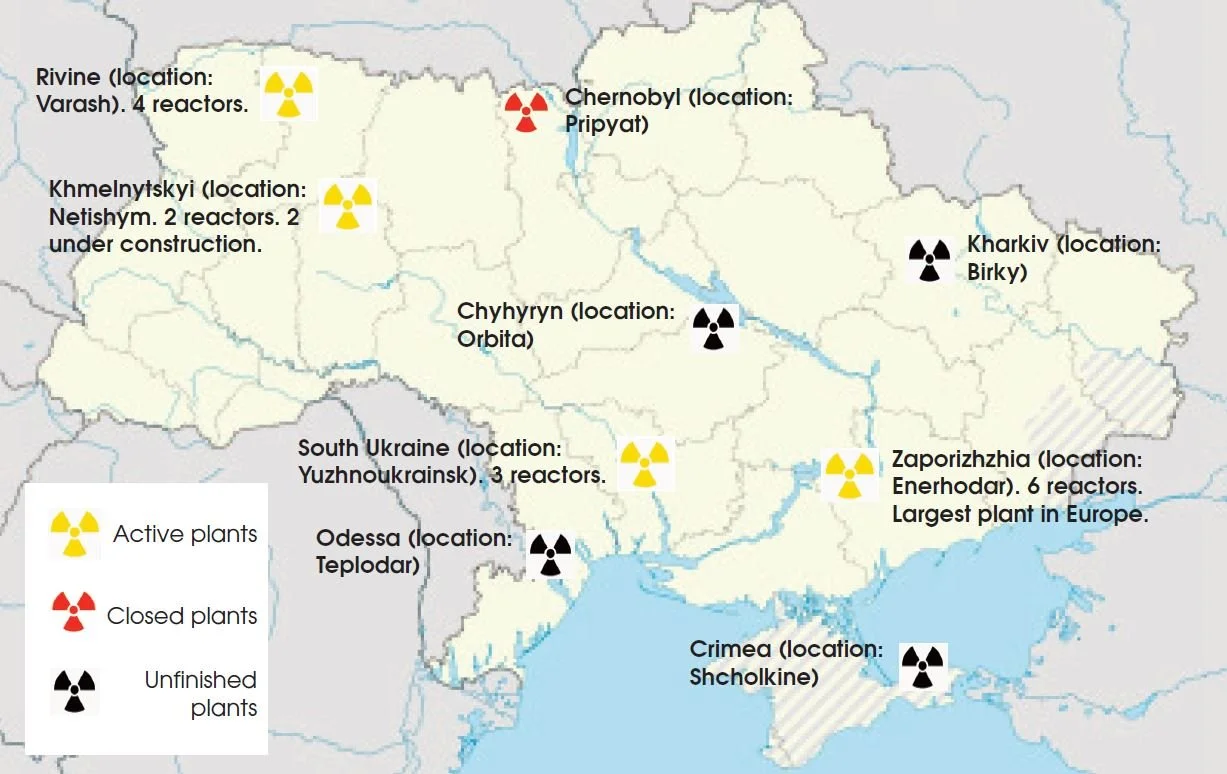

We shall also examine the additional threat of proliferation of nuclear weapons through the spread of nuclear power technology which means that, by the end of this century, about 40 countries will have the capacity to produce nuclear arms.

The Beginnings of Proliferation, the Incentives and the Dangers

It was inevitable that the American monopoly of nuclear weapons at the end of World War II would not last very long. When the Soviet Union caught up, this intensified the Cold War. Yet, in spite of the rivalry between the two superpowers, there has existed, since the death of Stalin and the beginnings of detente, a common desire to act jointly as the world’s policemen and to control negotiations on disarmament. This was reflected in their joint chairmanship of the Geneva Disarmament Committee. Though there are obvious conflicts of interest in many regions of the world; on disarmament, they speak the same language. They see themselves as the custodians of world order; and the cohesion of their alliances remains more important than progress towards disarmament. This is why they have tried, and succeeded, to keep negotiations on a bi-lateral or tri-lateral, rather than on a multilateral basis. (The negotiations in the early 60s on the partial Test Ban Treaty and current negotiations for a Comprehensive Ban are restricted to the US, the USSR and Britain). It is significant that in all the talks that have gone on they have never been ready to accept anything more than minimum control of rearmament. During the negotiations on the Non-Proliferation Treaty they both rejected pressure for a reduction of nuclear weapons which they demanded from the others. They have never been willing to accept what is called now “A Low Posture” and which was initiated in the 60s by Professor Pat Blackett as a “Minimum Deterrent” policy. This called for a reduction of their nuclear weapon stockpiles to 100 missiles, capable of inflicting ‘’unacceptable damage”; as a step towards the elimination of all nuclear weapons. The NNWS, during the negotiations on the Non-Proliferation Treaty, pressed for a similar limitation through a moratorium on both quantitative and qualitative development of nuclear arms - but with no success.

Proliferation began in Britain and then in France. The main incentive for both countries was prestige. Both believed that by acquiring even, a small nuclear arsenal they established themselves as major powers. Both of them Alva Myrdal suggested “are in a sense compensating for the loss of status as colonial empires”. The Americans were no;t too happy. McNamara, then Secretary for Defense, said that small independent deterrents were dangerous, expensive, incredible and prone to obsolescence. Nevertheless, the United States helped Britain to acquire their four Polaris submarines - and Mrs Thatcher is now asking them for Trident submarines to replace them.

But, for de Gaulle, there was another incentive. He did not trust the American “nuclear umbrella”. He did not believe that the United States would use its nuclear weapons in defence of Europe at the cost of the destruction of its own cities and the death of millions of Americans. This lack of faith in the US “nuclear umbrella” has even, recently, been encouraged by Kissinger. Current moves to establish medium range nuclear missiles in Europe must also be seen as an intention to limit, if possible, any nuclear war to Europe, but including Russia.

China’s motives were, partly, the same, but here there was also another incentive, regional confrontations, between China and the USSR and between China and India. This applies also, now, to two countries which are believed to have produced some sort of nuclear device - Israel and South Africa (and there is little doubt that South Africa recently tested a nuclear weapon in the South Atlantic).

It is hardly necessary to stress the dangers of spread. They are listed in the book produced by the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), Postures for Non-Proliferation: Arms Limitation and Security Policies to Minimize Nuclear Proliferation. Any increase in the number of NWS can have a domino effect. It increases the risk of an accidental nuclear war, and the risk that local wars can escalate into a nuclear war, involving the superpowers. It encourages the nuclear arms race between the superpowers. It makes disarmament negotiations more difficult. The use of a nuclear weapon by a small nuclear power would break the present ‘taboo’ on their use. There is the risk that they may be acquired by a ‘crazy’ state, or by a state where a new ‘crazy’ government takes over. It complicates international politics and fuels regional rivalries. The more nuclear weapons there are and the more countries which have them, the greater the danger that they will eventually be used. But here we must stress that it is not only the number of states armed with nuclear weapons that matters but also the steady increase in the size and quality of the stockpiles of the superpowers. That is also a form of proliferation.

The 1965-1968 Negotiations

If we are to decide correctly on which issues we should concentrate during the Second Review Conference of the NPT, it is important to study and analyse the negotiations which took place between 1965 and 1968 and during the First Review Conference.

During the negotiations on the Treaty there were major disagreements between the NWS and the NNWS on three points:

1. What measures for the limitation of nuclear arms and for disarmament should be included in the Treaty as a counterpart to the renunciation of nuclear weapons by the NNWS?

2. What types of security guarantees should be given to the NNWS by the NWS?

3. The duration of the Treaty, and the provisions for review and withdrawal.

The procedure was as follows: at the opening of the conference, the two superpowers tabled two draft treaties, as a basis for discussion. On August 8, 1967, after two years of discussion, two more draft treaties were tabled, with minor changes. In January, 1968, two more identical treaties were tabled. Two more identical treaties followed in March 1968. These were linked to the text of a Security Council resolution on guarantees. Revised versions of both were tabled in May 1968. The Treaty then was approved by the UN on June 12, 1968 and, a few days later, the Security Council passed the resolution. The Treaty came into operation in 1970.

Neither of the two first draft treaties contained any reference to collateral measures. They both argued that these were unimportant compared with the urgent need to stop spread. This was stressed by Lord Chalfont, speaking for Britain:

“I would ask the non-aligned delegations to ponder on this point in case it turned out to be impossible to get agreement among the nuclear powers to some measures of reduction ... I should like to ask the non-nuclear Powers most seriously whether, if this position is reached - a treaty within our grasp, but the choice of collateral measures still in dispute - it would not still be in the interest of every non-nuclear State to call a halt to the spread of nuclear weapons even if the nuclear weapon Powers themselves had not actually begun to disarm.”

Ambassador Foster of the US referred to the demand that the Treaty contain obligations on the nuclear weapon States to cease all nuclear weapon tests, to halt production of fissionable material for weapons, to stop making nuclear delivery vehicles, or “even to begin nuclear disarmament”, as a hurdle which was getting in the way.

The argument, on all three points at issue, went on for two years. Counter-proposals were tabled by India, Sweden, Brazil, Burma, Egypt, Morocco and Nigeria. India, for instance, put forward five points.

1. An undertaking by the nuclear powers not to transfer nuclear weapons or nuclear weapons technology to others;

2. An undertaking not to use nuclear weapons against any countries which do not possess them;

3. An undertaking through the United Nations to safeguard the security of countries which may be threatened by Powers having a nuclear weapons capability or about to have a nuclear weapons capability;

4. Tangible progress towards disarmament, including a comprehensive Test Ban Treaty, a complete freeze on production of nuclear weapons and means of delivery as well as substantial reduction in the existing stocks; and

5. An undertaking by non-nuclear Powers not to acquire or manufacture nuclear weapons.

India also suggested a two stage Treaty, in which the collateral measures came first. Sweden proposed, as essential collateral measures, a comprehensive test ban treaty and a cut off in the production of fissile material for weapons, together with an agreement on non-dissemination.

By early 1967, it was clear that neither of the two superpowers would accept any related disarmament measures in the Treaty. Article VI contained some vague references which the NNWS saw as binding, legally, but which the nuclear powers did not. It contained only a vague statement of intention. There is “no balance” Indian Ambassador Trevede said, “between a platitude on the one hand and a prohibition on the other.”

On security guarantees, in their first, 1965 drafts, the US favoured positive guarantees, that is, they offered the states agreeing not to acquire nuclear weapons the ‘protection’ of their ‘nuclear’ umbrella; while the USSR offered negative guarantees, a promise not to attack with nuclear weapons States that were signatories to the Treaty. There were also arguments on the question of de-nuclearised zones. The 1967 draft treaties contained a paragraph in the Preamble “noting that nothing in this Treaty affects the right of any group of States to conclude regional treaties in order to assure the total absence of nuclear weapons in their respective territories”. The 1968 identical draft treaties contained a new Article VII: “Nothing in this Treaty affects the right of any group of States to conclude regional treaties in order to assure the total absence of nuclear weapons in their respective territories.” But there were no references to broader security guarantees.

On duration, review and withdrawal, in their 1965 treaties, both the US and the USSR wanted an unlimited, indefinite duration to the Treaty, subject to withdrawals, but no further conferences unless demanded by two-thirds of the parties to the Treaty. In the years that followed the NNWS continued to press for regular reviews in order to monitor the extent to which the NWS had fulfilled their obligations under Article VI. It was only in the last stages of the negotiations that the US and the USSR agreed to periodic review conferences, at intervals of 5 years. This was put into Article VIII.

Here we give four paragraphs from the Preamble, Articles VI and VII and Paragraph 3 of Article VII which represent the very meagre victories achieved by the NNWS:

From the Preamble

“Declaring their intention to achieve at the earliest possible date the cessation of the nuclear arms race and to undertake effective measures in the direction of nuclear disarmament,

“Urging the cooperation of all States in the attainment of this objective,

“Recalling the determination expressed by the Parties to the Partial Test Ban Treaty of 1963 in its preamble to seek to achieve the discontinuance of all test explosions of nuclear weapons for all time and to continue negotiations to this end,

“Desiring to further the easing of international tension and the strengthening of trust between States in order to facilitate the cessation of the manufacture of nuclear weapons, the liquidation of all their existing stockpiles, and the elimination from national arsenals of nuclear weapons and the means of their delivery pursuant to a Treaty on general and complete disarmament under strict and effective international control.”

Article VI: “Each of the Parties to this Treaty undertakes to pursue negotiations in good faith on effective measures relating to cessation of the nuclear arms race at an early date and to nuclear disarmament, and on a Treaty on general and complete disarmament under strict and effective international control.”

Article VII: “Nothing in this Treaty affects the right of any group of States to conclude regional treaties in order to assure the total absence of nuclear weapons in their respective territories.”

Article VIII, Para 3: “Five years after the entry into force of this Treaty, a conference of the Parties to the Treaty shall be held in Geneva, Switzerland, in order to review the operation of this Treaty with a view to assuring that the purpose of the Preamble and the provisions of the Treaty are being realised. At intervals of five years thereafter, a majority of the Parties to the Treaty may obtain, by submitting a proposal to this effect to the Depositary Governments, the convening of further conferences with the same objective of reviewing the operation of the Treaty.”

It could be said that the only part of these pious assurances which has been put into practice is that concerning strict international inspection. This is now assured by the satellites of the superpowers sweeping around through space. The Security Council Resolution had three points:

“l. Recognises that aggression with nuclear weapons or the threat of such aggression against a non-nuclear State would create a situation inwhich the Security Council, and above all its nuclear-weapons State permanent members, would have to act immediately in accordance with their obligations under the United Nations’ Charter;

2. Welcomes the intention expressed by certain States that they will provide or support immediate assistance, in accordance with the Charter, to any non-nuclear-weapon State Party to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons that is a victim of an act or an object of a threat of aggression in which nuclear weapons are used;

3. Reaffirms in particular the inherent right, recognised under Article 51 of the Charter, of individual and collective self-defense if an armed attack occurs against a Member of the United Nations, until the Security Council has taken measures to maintain international peace and security.”

After it was passed, three of the nuclear-weapon States, the US, the USSR and Britain, made identical unilateral statements to the same effect. All this, of course, was utterly meaningless. Four of the five nuclear-weapon States in the security Council had vetoes, and the fifth, People’s China, now also has a veto.

One immediate result of the deficiencies of the Treaty, as Alva Myrdal points out, was that, between 1968 and 1970 when the Treaty came into force, only four Powers that had the capacity to produce nuclear weapons had ratified: Canada, Sweden, East Germany and Australia. West Germany, Italy, Belgium and the Netherlands ratified only a few days before the First Review Conference, and Japan in May 1976. Among those refusing were Argentina, Brazil, Egypt, Israel, Spain, South Africa and Pakistan.

She cites five crucial points which illustrate the lack of balance between obligations and benefits: l. The pledge in Article VI to cease the nuclear arms race is still unfulfilled and is unlikely to be honoured in the foreseeable future; 2. The obligation in Article III for the NNWS to accept safeguards, as set forth in an agreement to be negotiated and concluded with the International Atomic Energy Agency ... for the exclusive purpose of verification, etc. is one-sided. It has been implemented by most of the States that have ratified, but not by the US and Britain; 3. There is an undertaking in Article IV, combined with Article I that Parties to the NPT would be favoured with regard to the supply of nuclear technology. This has not happened; 4. Article V promised that the benefits from peaceful nuclear explosions would be made available to signatories to the Treaty at low cost, through a special international agreement and an international body. No such agreement has been reached. No such body has been set up; 5. The security guarantees in the Security Council Resolution restricts rather than adds to their obligations to render assistance. As we have already pointed out, at that time four of the five nuclear armed Powers had a veto. All five now have the veto.

The First Review Conference: 1975

This was seen by most of the NNWS as an opportunity to attack the NWS for their failure to implement Article VI, and to strengthen their obligations on limitation and disarmament measures. In this, they failed miserably. The scales were weighed against them in every way. The Conference was financed by the major superpowers. They conferred in London before it took place. The United States showed its contempt by conducting a big nuclear weapon test during the conference.

The NNWS wanted three types of documents agreed: a General Declaration; a Resolution covering substantive items on the agenda; some additional Protocols to the Treaty.

After 26 days of argument, there was no agreement on any of these. Only a compromise was agreed, a draft Final Declaration to be adopted by consensus, amplified by interpretative statements. There was no agreement on two resolutions and the Protocols which the NNWS tried to add to the Treaty were only put into an annex to the Declaration.

The NWS refused to consider any proposals imposing additional obligations on them. They insisted that they were fulfilling Article VI, that there had been progress, both bilateral and multilateral - and they cited the Sea Bed Treaty, the Treaty banning Biological Weapons, the Anti-Ballistic-Missile Treaty, and the Strategic Arms Limitation Talks (SALT).

The Soviet Union pushed its own policies: the demand for a World Disarmament Conference; that Resolution 2936 of the Security Council on the renunciation of the use or threat of force in international relations and the permanent prohibition of the use of nuclear weapons be made legally binding. Both the US and the USSR stressed their commitment to the SALT negotiations. US Ambassador Ikle claimed that:

“In the five years that had elapsed since the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons had come into effect, far more had been accomplished in the control of nuclear arms than in the preceding twenty five years. The Treaty had proved to be both a prerequisite and a catalyst for progress towards nuclear disarmament. The disarmament process was under way and it was up to all States to encourage and sustain it.”

These protestations were rejected by the NNWS. They said that SALT had only ratified pre-existing trends and had permitted substantial quantitative and qualitative improvements, institutionalising the nuclear arms race. Ambassador Roberts of New Zealand said:

“It is small wonder that the countries outside the Treaty remained unconvinced that the nuclear-weapon parties were serious in their intention to give effect to their undertakings. The most valid test of progress was surely to ask whether or not there were fewer nuclear weapons in existence today than there had been in 1970; whether or not there had been any abatement in nuclear weapons testing during that period; and whether or not there had been any halt in the further refinement and sophistication of nuclear weapons. The answer to all three questions was patently no. The limited and peripheral agreements negotiated so far gave little ground for reassurance.”

The NNWS emphasised that they were obliged to fulfill their obligations when they signed the Treaty, while the NWS were not bound by any specific date. If horizontal non-proliferation was to be achieved, they insisted that the NWS had not only to pursue but to agree on some collateral measures and they quoted, in particular: a Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty; a cut off of the production of fissile material for weapons; and a limit on missile test flights.

Three important draft protocols to the Treaty were put forward. The first was sponsored by 20 NNWS (Bolivia, Ecuador, Ghana, Honduras, Jamaica, Lebanon, Liberia, Mexico, Morocco, Nepal, Nicaragua, Nigeria, Peru, the Philippines, Romania, Senegal, the Sudan, Syria, Yugoslavia and Zaire). It was designed to lead to the complete cessation of all nuclear testing.

“to decree the suspension of all nuclear tests for a period of ten years, as soon as the number of parties to the Treaty reaches one hundred; ... to extend by three years the moratorium ... each time that five additional States become party to the Treaty, ... (and) to transform the moratorium into a permanent cessation of all nuclear weapon tests, through the conclusion of a multilateral treaty for that purpose, as soon as the other nuclear weapon States indicate their willingness to become parties to the said treaty.”

Protocol II sponsored by the same States, except for the Philippines, called for substantial reductions in the nuclear weapon capabilities of the United States and the Soviet Union:

“To undertake, as soon as the number of Parties to the Treaty has reached one hundred (a) to reduce by fifty per cent the ceiling of 2,400 nuclear strategic vehicles contemplated for each side under the Vladivostok accords; (b) to refrain from first use of nuclear weapons against any other non-nuclear-weapon States Parties to the Treaty.

They undertake to encourage negotiations initiated by any group of States parties to the Treaty or others to establish nuclear weapon free zones in their respective territories or regions, and to respect the statute of nuclear weapon free zones established.

In the event a non-nuclear-weapon State Party to the Treaty becomes a victim of an attack with nuclear weapons or of a threat with the use of such weapons, the States Parties to this Protocol, at the request of the victim of such threat or attack, undertake to provide to it immediate assistance without prejudice to their obligations under the United Nations Charter.”

There were also a number of resolutions.

Since the major superpowers refused to accept any of these Protocols or draft resolutions, or to give any additional guarantees, the Conference ended with a useless final declaration, drafted by Sweden’s Ambassador, Inge Thorsson. This only outlined their concerns and avoided specific criticisms of the major nuclear powers. It outlined the concerns of the NNWS, welcomed the various agreements on arms limitation and disarmament that have been reached, and urged greater efforts by all, but especially the NWS, “to achieve an early and effective implementation of Article VI of the Treaty. It urged limitations on the number of underground tests pending a halt to all of them.” It also appealed to the United States and the Soviet Union to try to conclude the SALT agreement outlined in Vladivostok, which at the end of 1979, had still not gone through the US Congress.

The Second Review Conference: 1980, Prospects and Priorities

Since the First Review Conference in 1975, there have been some important changes in the disarmament process. The Conference of Non-Aligned Countries has become more active and radical. They sponsored and initiated the Special Session on Disarmament of the UN General Assembly in 1978. Their Co-ordinating Bureau produced a Working Paper for the Preparatory Committee which fiercely condemned the lack of progress:

“Since disarmament negotiations within the framework, or under the auspices of the United Nations, as well as the regional and bilateral negotiations, have not produced the expected results in most cases, it is necessary to exert fresh efforts to overcome this situation. The contradiction between the urgent necessity to curb the arms race and the stand-still in disarmament efforts is becoming increasingly intolerable. Expenditure, particularly on the development of new and more sophisticated weapons systems, is spiralling. The continuation of the arms race poses a direct threat to international peace and security and slackens economic social development. Disarmament has thus become one of the most urgent international problems, requiring the greatest attention.”

It included a wide range of concrete proposals, rejecting “partial measures” and calling for rapid progress to total nuclear disarmament and to general and complete disarmament.

While the Final Declaration was a compromise document accepted by consensus containing far too many platitudes, there were some important changes in the disarmament process. The two major superpowers, the US and the USSR, ceased to be Joint Chairmen of the Geneva Disarmament Committee. The Committee was enlarged and its plenary sessions were opened to the public.

The Special Session also encouraged a considerable upsurge in activity on disarmament by non-governmental organisations, and in international co-operation between them on a much wider scale - and this has continued.

But it is important not to be too optimistic about these changes. SALT negotiations are still bilateral, between the US and the USSR, though if we ever get as far as talking about SALT III, the NATO and Warsaw Pact powers may be included. Nevertheless, there are greater opportunities for action now both by the NNWS and by movements, and the Second Review Conference is one of these.

But there is also a [negative] side to the picture. Developments in the Middle East - on energy, and in Iran, with the hostages still held - have led to a massive increase in the belligerency not only of the hawks but of the American public in general. SALT II has failed to get through Congress this year, may fail again in 1980 and we cannot be sure that it will even be accepted after the next Presidential election. Direct intervention by US forces, banned since Vietnam, is now once again acceptable, especially in defence of American supplies of energy in the Middle East. Military budgets are being increased, in the United States, in Britain, by both NATO and the Warsaw Pact, including the Soviet Union. The Conservative Government in Britain is aiming to replace its ageing Polaris submarines with the much more powerful Tridents. Defence Minister Pym has stated on television that, if necessary, they would be used independently of the US, though he was followed by a retired General who insisted that that would be tantamount to suicide.

In addition there is the new threat of the deployment in Europe of medium rang: nuclear missiles, which has, in fact, already begun. This involves the basing of 108 Pershing II missiles in West Germany and 464 land based Cruise missiles, which are sub-sonic, pilotless and very accurate flying bombs - 160 in Britain, 112 in Italy, 96 in West Germany and, in the original US proposal, 48 in both Belgium and Holland. The United States would meet the cost of production and they would remain under US control. Only one finger on the button.

These proposals have alarmed the Soviets though they themselves have started to deploy SS-20 missiles which can reach any European cities or installations. On October 4, Brezhnev announced the unilateral withdrawal of 20,000 Soviet forces and 1,000 tanks from Central Europe. This has begun and was highly publicised. But they have not yet made any proposals for the withdrawal of their SS-20s. But they have made it clear that if the proposal was accepted by NATO which, more or less, it has, they would still be ready to talk.

The NATO countries are not united on the proposals. While Britain, West Germany and Italy accepted (Schimdt got it through his party conference by putting it forward as a means to obtain talks, the Italian Parliament agreed, with few signs of opposition from the Italian Communist Party, the British parliament was not even allowed to discuss it); the Dutch parliament rejected it and their Prime Minister, Andreas Van Agt, faced a situation that, if he ignored their decision, his government might fall, since several members of his Christian Democrat Party voted against it, and there is strong opposition from the Dutch public and from the Churches. In Belgium, the coalition government also had problems since two socialist parties in it were opposed. There was also disquiet in Norway and Denmark though neither country was directly involved as it was not proposed to base any of the new missiles on their territory.

Finally, at a meeting of NATO Foreign and Defence Ministers on December 12 and 13, NATO agreed to press ahead, though the Dutch, the Belgians and the Danes had proposed a delay. Their reservations were submerged by a compromise decision that accepted the deployment of the missiles in West Germany, Italy and Britain. The Dutch Defence Minister, pressed his doubts, hoping, no doubt, to satisfy his opposition at home:

“The Netherlands agrees that there is a need for a political and military answer to the threatening developments in relation to Soviet long-range theatre nuclear forces, particularly the SS 20 missile and the Backfire bomber. In view of the importance we attach to arms control and to the zero option as the ultimate objective in this field, the Netherlands cannot yet commit herself to the stationing of ground-launched Cruise missiles on her territory. The Netherlands will take a decision in December, 1981, in consultation with the Allies, on the basis of the criterion whether or not arms control negotiations have by then achieved success in the form of concrete results. The Netherlands believes that any stationtioning of new weapons systems on Dutch territory should result in a reduction of the Netherlands existing nuclear tasks. The Netherlands Government proceeds on the assumption that SALT II will have been ratified by December, 1981.”

But, since they agreed to contribute £250 million to the cost of the infrastructure required, this enabled the decision to be publicised as ‘unanimous’.

The Belgian Government agreed both to production and deployment, but their decision was to be reviewed in 6 months time - which allowed them to try and pacify the opposition at home.

As a counterpart to this, the NATO meeting agreed to withdraw 1,000 of their present nuclear warheads in Europe, many of which are obsolescent and, of course, have a much smaller range; and the new missile will be counted within that reduced level, that is, 6,000. They have also agreed to undertake negotiations, as soon as possible, for mutual reduction of nuclear weapons in Europe. Secretary of State Vance said that he hoped they would start within a few months, and that they will be held as part of the next round of SALT Talks - a somewhat pious proposal, since SALT II is still not ratified. The NATO meeting set up a group to participate in any such talks.

At their meeting on December 13, the NATO Ministers also agreed on new proposals to be tabled at the Vienna Talks on troop reductions in Europe. They proposed, as a first phase, a withdrawal of 13,000 US troops and 30,000 Soviet troops - based on a West German proposal. These are lower than the original NATO proposals for the first stage. The problem that has stymied progress in Vienna is that the US and the USSR have not been able to agree on the number of Soviet troops in Central Europe. NATO says there are 987,000, the Warsaw Pact insists that the figure is 837,000.

We can be sure that the United States and its allies will cite these proposals as signs of progress during the Second Review Conference - though what the NNWS are demanding is not proposals, but agreements.

Priorities

In the light of all this past history, the most important priorities for pressure on governments, and especially on the NWS, are as follows:

1. A Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty

Another Session of the Tripartite Talks (the US, USSR and Britain) has just ended with no significant progress. There has been a year of virtual stagnation. The Partial Test Ban Treaty was signed in 1963. Since then, these three have conducted only underground tests. France, since 1975, has also tested underground, though there is grave doubt that there may be leaks from their sites in Polynesia into the ocean. In 1974 the United States and the Soviet Union signed the Threshhold Test Ban Treaty, prohibiting underground tests of more than 150 kilotons. They also promised to restrict them.

According to the 1979 SIPRI Year Book, there have been 1,165 test explosions between 1945 and 1978, and 667 since the Partial Test Ban Treat (PTBT) was signed - most of them designed to improve the efficiency of nuclear weapons. More than 90 per cent of them were carried out by the original three signatories to the PTBT - 60 by the Soviets, 37 by the Americans, and 3 by the British. In 1979, the Soviet union conducted more tests than in any year since 1963. The Chinese figure is 8.

But the Russians have made some concessions. They agreed to include peaceful nuclear explosions in the Treaty and accepted the principle of on-site inspection, to accept 10 seismic installations in the Soviet Union. The US also agreed to 10. The Soviet Union also proposed 10 for Britain, which was refused, because they test in the United States. So the USSR proposed 1 in Britain and 9 in various British dependencies, such as Hong Kong and the Falkland Islands. Britain insists on offering only 1 site at Eskdalemuir, where one already exists. There are also disputes over the question of renewal after a first 3 year moratorium.

But the most serious obstacle is in the United States where the military believe that a comprehensive ban would undermine their technological superiority - and that the Russians would cheat. It is certainly doubtful whether SALT II and a Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty could get through Congress during 1980.

2. The Establishment of De-nuclearised Zones with Guarantees from the NWS not to Deploy or Use Nuclear Weapons in such areas

This proposal is prejudiced by the increasing militarisation of both the Pacific and Indian Oceans, where there is considerable pressure for them, both from public opinion and from some of the littoral States.

3. Negative Guarantees From NWS Not to Attack NNWS With Nuclear Weapons

So far, the superpowers have produced only the Security Council Resolution of 1975, which is nullified by their vetoes.

4. A Moratorium on Research, Development, Manufacture and Deployment of New Nuclear Weapons and Their Delivery Systems

The Mobilisation for Survival in United States has been collecting signatures for such a moratorium, including a moratorium on nuclear power. It will be presented to Congress in April, 1980.

5. Cuts in Military Budgets and the Diversion of the Funds to Aid for Developing Countries

This has been proposed by the Soviet Union. At present, they are all increasing.

6. A Moratorium on the Production and Deployment of Medium Range Nuclear Missiles in Europe, Pending Negotiations

Here we must emphasise that the increase in the range of theatre nuclear missiles in Europe, which has been in the pipe line for some time, produces a new situation. Previously, the comparative small range of tactical nuclear weapons in Central Europe made it possible, as de Gaulle believed and Kissinger has recently confirmed, that a limited nuclear war could occur in Central Europe, leaving the territory of the US and USSR untouched.

Even such a ‘limited’ war would wipe out Europe. Schmidt, in 1971, realised this. In his book, The Balance of Power: Germany’s Peace Policy and the Super Powers, (William Kimber, London, 1971, p.196) he recognised that such a war would lead rapidly to the destruction of Europe. Even a brief and locally limited war could mean 10 million deaths and cause total destruction of Germany as an industrial society, according to Carl-Friedrich v. Weizsacker. Yet as Alva Myrdal points out in her book, The Game of Disarmament, p.43/44:

“What are the political and public reactions to these obvious dangers. The peoples of Europe - West, East and neutral - have not been kept much aware of what is in store for them if the superpowers rivalry leads to a military confrontation in Europe. There has been a carefully kept official silence as to the consequences. Only once, in 1955, when a NATO military field exercise, ‘Carte Blanche’, resulted in 1. 7 million Germans ‘killed’ and 3.5 million ‘incapacitated’, was a short-lived furore caused ...

Since 1967 there has been little public discussion about any fundamental change in the policies of nuclear defence for Europe, little of the early clairvoyant anxiety of Helmut Schmidt. West European official postures have become frozen in a kind of frozen approval of the status quo.”

The new proposals, and the increase in the range of the nuclear missiles do not mean that Europe would be spared. But they do mean that the Soviet Union would not. The United States would be out of range, but not the USSR. This, no doubt, explains their current anxieties. (Though, in our opinion, it is doubtful whether a nuclear war which began in Europe could be restricted to a medium range missile exchange).

Some Final Points

We haven’t dealt here with the question of ‘vertical’ proliferation which, to put it in simple English, means increase in the quantity and quality of the nuclear arsenals of the superpowers. The main contention of the NNWS in all these negotiations is that such ‘vertical’ proliferation cannot be separated from the question of ‘horizontal’ proliferation the spread of nuclear weapons to more and more States.

As we have already stressed, prospects can hardly be called good. Relations between superpowers and States are increasingly unstable. More arms, nuclear and conventional are being produced, deployed and sold. But there is one argument which we ought to use in trying to educate public opinion and in promoting support for disarmament. It is still argued by States that possess nuclear weapons, that they are a deterrent and they quote as proof of this that no nuclear weapons have been used since 1945. But this does not mean that wars have been eliminated. 25 million people have died in conventional wars since World War II. Millions more have died for lack of food and medical care the money spent on arms could have provided.

But we must also stress that all this money has been spent to no purpose. The possession of nuclear weapons by the United States did not prevent a stalemate in Korea, they did not save France or the United States from defeat in Vietnam. The Soviet arsenals did not prevent them being thrown out of Egypt. And all their nuclear arms cannot help the United States to rescue 50 hostages in Iran. One can also ask the new nuclear powers, Israel and South Africa, where or how they could use them? We have to convince the people in the nuclear armed states, and those in states with nuclear ambitions, that they are useless and very expensive playthings, that they do not bring security, that more of them mean less security, that they and their children can only be safe if they are totally abolished.